on

The membership of Lancashire libraries

When I proposed the idea of data storytelling in library services, Lancashire were one of the first to volunteer, as well as suggesting areas of their data they’d like to explore. One of these was library membership and usage.

Lancashire and its libraries

Lancashire is a county in North West England. The name can refer to different things and we shouldn’t confuse the ceremonial county with the county council. Lancashire County Council is one of 3 ‘upper-tier’ local authorities within the ceremonial county, alongside Blackburn with Darwen, and Blackpool.

The population of Lancashire County Council is about 1.2 million and the libraries serving that population are Lancashire Libraries.

Lancashire Libraries deliver statutory, front-line library, information and digital services to communities from 64 buildings, 6 mobile library vehicles and through a Home Library service. They offer a free Digital Library including eBook, eAudio, newspaper and magazine download service. Public computers and WiFi are available without charge in all buildings. A library service is delivered at 5 Lancashire prisons. The School Library service supplies subscription-based reading and library services to primary schools, special schools, nurseries and children’s centres.

Lancashire are a library service that have always been keen to engage with data projects; they understand their data, and want to do more with it. Carolyn Waite, the Information Development Manager had also previously been involved in projects such as the Library Data Schemas, and round table data discussions with sector leaders.

When a user joins Lancashire Libraries, the library service requests a small amount of information: Name, Local library, Date of birth, Address, Telephone number and/or email address.

One of the most useful pieces of data is one that gives the least direct information: the user’s postcode. A postcode doesn’t describe an individual, but it tells us a lot about a place. In society, we still use the term postcode lottery to describe unequal provision of services such as healthcare and education, within different communities. Differences in socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age, and other demographic data are also stark between different areas.

When analysing members we don’t want to pry into their personal lives. Their income, education level, and health shouldn’t be collected or analysed. But we can analyse membership by where people live, and look at the profile of those areas. It doesn’t mean that everyone who lives in that area is the same, but as long as we have a decent sample of people, we can start to gather insight.

What do library members do?

When considering a ‘library member’ we shouldn’t limit ourselves to traditional definitions of usage. CIPFA library statistics collect the number of ‘active borrowers’ across library services. This excludes anyone who is using a library for any other reason: computers, eBooks, eMagazines, etc.

While borrowing still remains the primary reason for library membership, we shouldn’t ignore other usage types. If we don’t consider other usage we miss opportunities for insight, and even simple cross-marketing.

If a service discovers it has communities who don’t borrow books, but seem to be using the library for other activities, that’s an opportunity to engage users when they are in the library. If a community seems to have little contact with the library at all, that may require further outreach activities outside of the library.

Lancashire libraries have strong data capability: Nick Wotherspoon was very familiar with the reporting capabilities of the different library databases and was able to generate postcode lists for members with the following usage types:

- Active borrowers of physical materials

- Active PNET users (users of the public network computers)

- Active digital users (ebooks/emagazines)

These were all taken from Summer 2024. A May 2024 report from Libraries Connected Ebook lending in public libraries, provides some data for different usage types across 28 library services across England and Wales. This will provide a useful baseline comparison for some of the findings.

Explorer maps

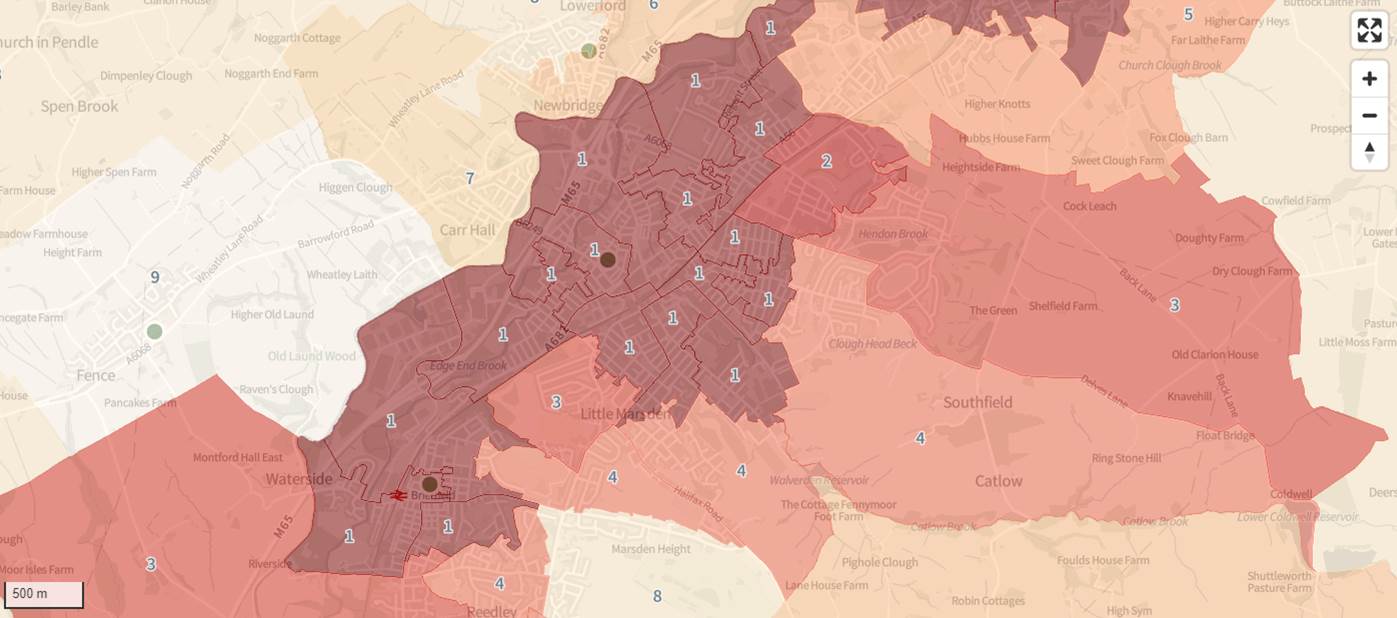

Exploring digital maps of Lancashire - this one highlighting high levels of deprivation in Brierfield

Exploring digital maps of Lancashire - this one highlighting high levels of deprivation in Brierfield

We’re familiar with people using maps for exploration, but perhaps less so for exploring data. Maps are a really useful way to gain insight from geospatial data (data related to places). It’s an instantly familiar visualisation method that can communicate the story behind data in a way that is intuitive - particularly for people who know the area in question.

Catherine Honnor, a library manager in Lancashire, did a brilliant job of transforming the postcode lists of membership types into counts of membership per LSOA, while keeping the postcode data within the library service.

Catherine also gave up time to look at this data on a digital map, which showed the different LSOAs in Lancashire, and shaded them to represent membership as a percentage of population. We also explored the map with the areas shaded by level of deprivation, which provided some useful context. More importantly, Catherine was also able to being essential local expertise to the findings.

That kind of local expertise proved the rule that when doing any data analysis it is important not to do it in isolation, without involving subject matter experts. The majority of the findings needed expertise to either confirm that it matched lived experience, or in some cases warn against making assumptions about data. A lot of the insight into the findings was also provided by Carolyn Waite.

People borrowing books

Lancashire active borrower lists define an active borrower as a registered user with at least one physical format issue transaction in the last 12 months. The active borrower count was about 100k out of the total population of 1.2 million (8%).

When looking across different areas in Lancashire, the lowest figures for active borrowers were 1% of the population, and the maximum was 21%. It really highlights the difference in engagement with library borrowing between different communities.

Even at the low end there are positives though. While areas of just 1% active borrowers are low, it’s encouraging to see there were no areas without any active borrowers. If you’re looking to increase usage in a community it’s good to know that you have some users in that area. Assuming about 1,500 people per LSOA, just 1% would be 15 people who can advocate for the service. Perhaps it’s a good opportunity for a refer a friend scheme?).

It’s also a positive indication for the service that borrowing can be greater than 20%. If all areas of the County got to that level, it would amount to over doubling active borrowing. When you consider that there are also the other active membership types (events, ebooks/emagazines, PNET) it’s clear that the potential for library membership remains a high percentage of the population.

The area with 21% active borrowers was an LSOA that fell on the south side of Parbold. I’ve found in other examples of this data analysis that communities with a local library have high active usage. That sounds obvious, but isn’t always reflected in policy - the theory often goes that many people can reach a library without necessarily having one locally. However, a community having a physical library (or mobile library stop) is a great way of increasing membership. It was no surprise to discover that Parbold has a thriving library, with regular events, and is open 5 days a week.

The librry at Parbold. Self-evidently a great library.

The librry at Parbold. Self-evidently a great library.

We compared the spread of active borrowers across the different deprivation levels of the LSOAs (using the ‘index of multiple deprivation’). We could see that this matched the general population across those different deprivation levels. This suggests that, in terms of borrowing in Lancashire libraries, there isn’t a significant bias to favour either areas of low or high deprivation.

We also looked at usage across different measures of how rural/urban each LSOA was, to see if there were any significant differences. Although generally uniform, there seemed slightly lower active borrowing in the Major conurbation areas (the biggest towns). Lancashire has 6 mobile library vehicles with hundreds of stops - it’s highly likely this coverage across the authority helps to ensure that rural borrowing isn’t disadvantaged.

People on the computers

In Lancashire, PNET is the term used for the People’s Network computers.

There were 47k active members who are PNET users. These seemed high - while less than half the physical borrowing counts it was by no means a small percentage.

Across different LSOAs this had a significant range of differences in terms of population: from 0% in some areas, to 16% in another. The area with 16% active PNET members was an area called Brierfield. Brierfield is an area of high deprivation, as well as having a high population of non-white ethnicity (38% Asian and 36% Muslim).

We looked at differences in the proportion of PNET users across different deprivation measures. 30% of the PNET users were from areas that have a multiple deprivation index of 1 (the areas with the very highest measure of deprivation on a scale of 1-10). This was a clear result that showed PNET users were significantly likely to be from high deprived areas.

To some extent this is proving an ‘obvious’ point. Most people would guess that people in highly deprived areas are likely to make use of library computers and the Internet available there, but it is still important to back this up by data. In our example of Brierfield, all the LSOAs around that area had a deprivation index of 1 (highly deprived), with one area showing PNET usage of 16% of the population. It’s a credit to the service provided by the library that they can demonstrate they are clearly meeting essential need shown by the most deprived communities.

The majority of PNET users were from urban areas, tending towards towns and cities. This was actually slightly down in the Major Conurbations. Again, this is where local knowledge was essential - Preston library had been temporarily closed with reduced PNET provision and usage and it is likely this would have skewed the usage away from the most urban areas.

People reading on their devices

There were 30k active ebook/emagazine users. Like PNET usage, this is less than physical lending but still a significant number of users. For context, the Libraries Connected report said that an average of 7% of registered library users are ebook borrowers. That’s a different measure, but these figures go further than that to show that ebook usage is close to 30% of the count of physical borrowers.

The variation between different areas was again significant - going from 0% in some neighbourhoods, to 8% in another, with an overall average of 2% of the population.

Usage looked to be slightly significantly less in areas of high deprivation. If users in those areas are more likely to use library PCs and Internet then they are less likely to have their own devices with which to borrow ebooks. Plus the type of digital activity is likely to be different.

A useful word of caution provided by Catherine was that we should consider that ebook/emagazine users in deprived households could well be sharing devies, and also library accounts. A highly affluent household may have multiple accounts and devices. This would skew the figures of ebook users more towards less deprived areas, but innacurately so.

This data could inform an action to target or market users in those highly deprived areas for mobile data schemes or tablet borrowing which would allow them to both browse the Internet as well as having access to ebooks and emagazines.

High levels of ebook usage seemed to be centred around bigger libraries. It was proposed that this could be due to digital champions in those libraries, or more focus and signage pointing people towards the ebooks service. An indication perhaps that a physical library service can still significantly increase digital usage.

The area with really high usage (8%) was Silverdale, a small affluent village. It is likely that a lot of residents speak to each other and will want to support their local amenities i.e. including the library. There will also be a high level of households having devices to enable e-book/audio, and residents will have a high % of good education and literacy. We can see this from the deprivation indicators where Silverdale has a multiple deprivation index of 9 - putting it amongst the 20% least deprived neighbourhoods in England.

Usage of these digital services was slightly higher in rural areas than urban areas.

Change over time

That was how the usage looked in the summer of 2024. But additional insight can be gained from observing how things change over time.

We next looked at a single type of usage (ebook/emagazine) and differences in the user registrations over two different timescales:

- Between April 2019 and March 2020

- Between April 2020 and March 2021

Those timescales give us a look before Covid-19 and then during it. One of the impacts of Covid for libraries was the shift to digital borrowing. There remain a lot of unanswered questions - did the people who registered for the ebook service during Covid match a similar profile to those who were registering previously? Was there truly a ‘shift’ to ebooks, or did it just accelerate the takeup for those users who would already be more inclined to use the service?

Firstly, the main takeaway was that the numbers were small, and it was difficult to spot anything that would give detailed insight.

| Year | Ebook registrations |

|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | 2880 |

| 2020-2021 | 3943 |

There is a significant increase in registrations (37%), but still overall low numbers. We mapped both sets of members across the County to see if there were clear patterns or ‘hotpots’ of registrations.

In 2019-2020 we didn’t see any clear patterns. At most the registrations amounted to 1% of the population of an LSOA, which would be around 10-20 people.

In 2020-2021 there were more areas that had higher registrations, though still only a maximum of 2% of the population. We found these were spots around the ‘Band A’ libraries (bigger libraries in big towns). The spread of registrations was otherwise uniform.

In both of the years there was a greater proportion of rural populations taking up digital services. While that echoed what was visible in the overall ebook active members, seeing it appear in consecutive years gave us a consistent pattern, rather than something that could have been caused by an anomaly of a particular year or programme.

The classification of an area as being rural is often used as a measure of digital exclusion/deprivation, so it’s good to see that there doesn’t appear to be a significant rural/urban divide in the usage of library digital services. That could be because being rural isn’t a valid measure of digital exclusion in Lancashire. Or it could apply to only small numbers of people; with active digital users only being a small proportion of an area, we won’t always be able to detect small numbers of people that are excluded. If usage continues to increase then keeping an eye on that proportion staying the same will be important.

It’s another postive indication for the library service that rural take-up of ebooks and emagazines is healthy, and shows that there are good communication to rural areas (including a significant mobile library service).